History

History began with the first humans and never ends because it is continuously being shaped by the entirety of human activity. As an academic discipline, history is about human societies, relationships and conditions and how these evolve over time.

Researchers at the Saxo Institute work on a wide range of topics in different time periods, places and fields of research and on the basis of varying theoretical and methodological approaches. This research contributes to our understanding of ourselves as conditioned by and creators of history. History as a discipline helps us to understand our own time and the processes that have shaped it.

Time periods

We can subdivide history into four main periods: ancient, medieval, modern and contemporary.

The core area for ancient history is the Greek, Hellenistic and Roman world from the Bronze Age to approximately 600 CE. There is a tradition of viewing the study of specific problems in a wider and often global perspective: the emergence of states, textile production, migration, warfare, long-distance trade, religion and cults. It is an approach that juxtaposes the historically specific with the historically general and the Greco-Roman world with other historical societies. As such, the study of antiquity provides an indispensable foundation for understanding ourselves and our own time. Research into ancient history is characterised by methodological pluralism. Specific skills and tools such as archaeology, epigraphy (the study of inscriptions), papyrology (the study of papyri) are deployed in productive interactions with modern theories derived from sociology, anthropology, economics, cultural history, etc. In addition to general, broad coverage of cultural, political, social and economic conditions, the Saxo Institute prioritises five particular themes: empires and comparative global history, migration, non-governmental organisations, textile research and trade and markets.

European Medieval history covers the period 500–1500 CE. The Saxo Institute conducts research into how the foundations of our culture were forged during this period. For example, we study cultural processes such as the transition from the Viking Age to the Middle Ages, the economic integration of Northern Europe into the Eurasian trade network, and the political and cultural developments during this period that laid the foundations for contemporary society. Institutions such as the monarchy, the Christian church, legislation, the University of Copenhagen and parliament all have their roots in the Middle Ages, as do our understanding of gender roles and identities, Denmark’s economic development, and its political and intellectual relations with other countries. As a result, Research at the Saxo Institute focuses not only on the study of events during the Viking era and Middle Ages but also on current conceptual developments and the use of history related to the Middle Ages.

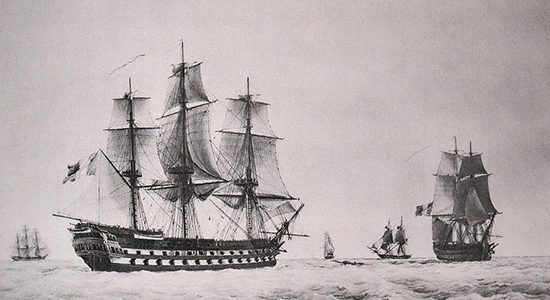

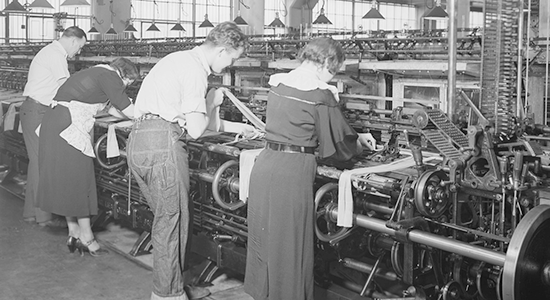

Modern history spans the period from 1500 to the end of the 19th century and is rooted in various research traditions, approaches and subject areas. It is, therefore, an extremely wide-ranging discipline. Modern history research can focus either on overarching processes of change – such as nation-building, industrialisation, population growth, Europeanisation, globalisation and changing worldviews – or on studies of culture, religion, gender, race, economics, urbanity, power, knowledge or social conditions. It can also focus on either overarching perspectives or close observations. However, despite the breadth and diversity of approaches, Modern history researchers at the Saxo Institute have one thing in common: They are all trying to understand the world before it became what we know today.

Research into contemporary history covers the 20th and 21st centuries and draws on diverse and wide-ranging research traditions, notably including political and economic history, the history of ideas, and cultural and social history. The contemporary historians at the Saxo Institute share an interest in historiographical, theoretical-methodological and empirical approaches to understanding the history of the past century or so. They also work alongside their fellow historians and academics in other departments. Geographically, they mainly study Western culture, i.e. Danish/Nordic, European and North American/transatlantic history, but the institute’s contemporary historical expertise also extends to the Middle East, Asia and Latin America.

Places

Historians at the Saxo Institute cover a wide range of topics from a variety of geographical areas. Many of them are primarily concerned with Danish history, often as part of wider regional or global contexts, while others focus specifically on global history.

The Danes have been a people and Denmark a state for at least a millennium, so continuity is a significant factor, but so too is change: The borders in the south and east have moved back and forth, relations with near neighbours (Germany, Norway and Sweden) have shifted between trade, alliances, federations, rivalries and war. Throughout history, Denmark has conquered and been conquered, been part of different political unions, been a regional power, a colonial power and a small state, has had different political systems and received political, cultural and technological impulses from all over the world. Historically, we have been a country of both emigration and immigration.

The 21st-century nation is, in short, the result of a long and tumultuous development, and it has always been one of history’s most important tasks to explain why and how the country we know today came into being. This was true in the infancy of historiography, which in the case of Denmark dates back to the High Middle Ages around 1200, and it is still true in the globalised world of today, in which nation-states face new challenges. History tells us that the solution is never a blinkered view but seeing national history in the wider context relevant at any given moment.

This means that the study of Danish history requires broad knowledge, an open mind and, in particular, critical thinking. Despite a globalised world, the nation remains the primary framework in which the past is interpreted and identities are created. Although our historical culture is also being globalised, global patterns are not replacing the national memory. Rather, national characteristics are merging with global ideas, a process that calls for a keen eye for both global and national narratives and a deep insight into the nation’s past.

Global history is about the connections, similarities and differences that have linked the peoples, regions and social units of the world from antiquity to the present. Questions relating to the emergence of the global present are central. For example, how do we explain global economic processes, and in particular why some parts of the world have achieved economic prosperity while others have stagnated? Global History research in the period after 1500 often focuses on European expansion. How have European colonial powers influenced and been influenced by non-European actors? How should we understand the formation of empires and their impact on the interaction between peoples and cultures? How have empires legitimised their supremacy over sustained periods? Global History also studies how geographical entities such as Europe, America, Asia and Africa have emerged and are reproduced ideologically and discursively. Geographical space is rarely taken for granted in global history research and is the subject of historical enquiry. This includes looking at how past actors have linked or separated spatial levels – the local, national, regional and global – which means that Global History is concerned with how economic, political, social and cultural spaces have been created.

Fields of research

The work done by historians at the Saxo Institute spans multiple periods, places and fields of research in political, economic, social and cultural history. History as a discipline has seen a continuous proliferation of new fields, including environmental history, conceptual history, colonial history, history of the use of history, history of emotions – and a long and ever-expanding list of others. New developments in the discipline are often related to current events and challenges facing society. The new fields of research typically draw on several of the overarching ones (political, economic, social and cultural history) and contribute to their transformation and development.

Political history at the Saxo Institute focuses on political power and how it is wielded by institutions, organisations and individuals; structural change processes and social and political movements; political language, communication and culture. Research in political history is diverse in terms of topics, approaches and sources but is driven by an ambition to understand the political as an overall phenomenon encompassing many different spheres. Focus areas include the Cold War, colonialism, decolonisation, international organisations, the climate and environment, political ideologies, building empires and nations, the welfare state and family relations. The emphasis is on the 19th century onwards. The research into political history at the Saxo Institute is conducted via individual projects, centres and research clusters.

Economic history studies the production, distribution and use of society’s resources. The tensions and dynamics in this field – ultimately its historical transformation – arise as individuals, families, organisations and state bodies act in the economic system on the basis of their different interests and incentives.

Economic history covers topics such as technology, business, trade, income, consumption, national budgets, money, cities and housing, etc. The major themes are growth and development, economic institutions, economic sectors and industries, individual companies, the international division of labour, wages, working conditions, income distribution, economic policy, business cycles, political economy and the history of economic ideas. Economic history focuses on the period from 1800 but can also include earlier periods, especially in terms of agrarian development and urbanisation. Economic history shares themes with political history, social history, global history and the history of ideas.

Economic history at the Saxo Institute does not have a specific programme, strategic profile or theoretical orientation but is defined by the individual researchers working in or near the field. Topics covered in recent years include the general economic history of Denmark, the history of the consumer, economic policy, post-1945 wages and labour markets, development aid, Americanisation, neoliberalism, colonial history, climate history and the history of landscape and agriculture

Cultural history is a multifaceted field that examines the imaginations, ideas, practices, rituals, creations, emotions and sensory experiences of people in the past. It ranges from studies of elite high culture to analyses of everyday life among people from all walks of life to the transformation – or stabilisation – of specific phenomena through cultural processes over time. One branch of cultural history uses a predominantly interpretive approach: Influenced by anthropological and other theories and deploying hermeneutic methodology, it attempts to make the intuitions, rationales, values and assumptions of people from the past accessible and understandable today. Another branch concentrates on deconstruction: Drawing on poststructuralist, feminist and postcolonial theory, it seeks to identify the discursive and social processes through which truths, identities and hierarchies are shaped and reshaped. In practice, many cultural historians combine both these approaches, and we also like to work across disciplines or make forays into political, economic and social history. Since cultural history can cover more or less anything – for example, the fight over a lottery in late 18th-century Copenhagen, disgusting smells in 19th-century Cairo or emotions linked to domestic violence in 20th-century Thisted – the only limit to the sources worked with the imagination of the researcher. For example, cultural historians at the Saxo Institute analyse personal archives, association archives, internet archives, correspondence, public debates, political speeches, instructional literature, artefacts, popular culture, divorce documents, court cases, memoirs, etc. Cultural history helps to denaturalise prevailing notions of what is natural or necessary, either by showing how our assumptions came about or by demonstrating that it has been possible to think, feel and act radically differently than we do today, all of which helps us better understand the present.

Interest in social history goes back to the statisticians of the 20th century who sought to document social conditions and problems. The classical discipline covered demographics, morbidity and mortality, nutrition, accidents, housing, working conditions, wages, consumers, unemployment, social security and pensions. More recent social history has largely focused on the exercise of power (economic, political and discursive). This power has mainly been wielded by established institutions such as prisons, hospitals, mental health units, kindergartens, schools and universities. In recent years, the focus has shifted towards social relations, networks, civil society, social cohesion, social movements, marginalisation and problem cultures. The research often adopts a comparative perspective on social relations in different social spaces within or between nation-states. The emergence, development, nature and problems of the welfare state constitute a specific area in which social historians have made a particularly valuable contribution. This has entailed a shift toward studying political priorities, means and measures. The focus of social hHistory research at the Saxo Institute is the period 1850–1950.

Theory and methodology

All historians at the Saxo Institute are engaged in theoretical and methodological questions related to their research topics.

Sources only reveal something about the past in the context of a historical problem, and work with historical sources is, therefore, always linked to theoretical and methodological considerations. This applies to all of the interwoven elements of the research process: articulating the problem, designing the analysis, as well as the reasoning and plot in the historiography. Theoretical and methodological reflection is, therefore, a natural and integral part of historical analysis. Source criticism, which plays an important role in the identity of history as a discipline, is today accompanied by a range of theoretical and methodological approaches and perspectives.

With regard to science theory, history shares problems with other parts of the humanities and the social sciences. What constitutes a scientific approach? What are the criteria for objectivity? What is the relationship between language and reality? A number of other science-theory questions are also of particular relevance to historians, such as the question of time and historicity, the relationship between the past, present and future, as well as collective memory and its political function.

- Autonomy and Expertise in International Administrations, 1940s-1970s

- Code and Conspiracy: Antisemitism in Denmark After 1945 (ASIDE)

- COPENHAGEN COMPLAINS: The Culture of Complaint and the Making of Eighteenth-Century Urban Order

- Eighteenth-Century Research Forum

- In the Same Sea: the Lesser Antilles as a Common World of Slavery and Freedom

- INNER_LEAGUE

- Link LIves - Historical Big Data

- Mapping Freedom: From slavery to freedom in the U.S. Virgin Islands

- Neoliberalism in the Nordics

- Racialised Motherhood: Documenting and Analysing Early Modern Discourses on Reproduction

- Radical Pietism in Northern Europe: Social Protest on the Verge of Modernity

- The Greek Revolution and European Republicanism, 1815-1830

- The Rhodes Centennial Project

Migrants and Membership Regimes in the Ancient Greek World

Funding: Independent Research Fund Denmark, Sapere Aude

Project period: 2020 - 2023

Contact: Christian A. Thomsen

The Copenhagen Associations Project

Funding: Carlsberg Foundation

Project period: 2011-2016

Contact: Vincent Gabrielsen

Visit the database Inventory of Ancient Associations Database (CAPinv)

The Politics of Family Secrecy

Funding: Independent Research Fund Denmark, Sapere Aude

Project period: 2018 - 2021

Contact: Karen Vallgårda

Researchers and lecturers

| Name | Title | Phone | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aarup, Kristian | Enrolled PhD Student | +4535325632 | |

| Bak, Sofie Lene | Associate Professor | +4535329460 | |

| Bang, Peter Fibiger | Professor | +4551299104 | |

| Christensen, Rasmus | PhD Fellow | ||

| Edelberg, Peter | Teaching Associate Professor | ||

| Engelhardt, Juliane | Associate Professor | +4535328483 | |

| Eriksen, Sidsel | Associate Professor | +4551299556 | |

| Fink-Jensen, Morten | Associate Professor | ||

| Fritzbøger, Bo | Associate Professor | +4551299759 | |

| Hjorth-Moritzsen, Line | Enrolled PhD Student | +4535333461 | |

| Ikonomou, Haakon Andreas | Associate Professor | +4535335625 | |

| Jahnke, Carsten | Associate Professor | +4551299737 | |

| Langen, Ulrik | Professor | +4527443416 | |

| Langkjær, Michael Alexander | Part-time Lecturer | ||

| Lilleør, Anton Sylvest | PhD Fellow | +4535321685 | |

| Lyngsted, Amalie Olga | Enrolled PhD Student | +4541717479 | |

| Løkke, Anne | Professor | ||

| Mariager, Rasmus Mølgaard | Professor | +4551299606 | |

| Møller, Jes Fabricius | Associate Professor | +4535335336 | |

| Nosch, Marie Louise Bech | Professor | +4523828021 | |

| Olden-Jørgensen, Sebastian | Associate Professor | +4551299653 | |

| Olsen, Niklas | Professor | +4551299676 | |

| Pelt, Mogens | Associate Professor | +4551299521 | |

| Rasmussen, Anders Holm | Associate Professor | +4535335769 | |

| Rasmussen, Morten | Associate Professor - Promotion Programme | +4529620550 | |

| Rud, Søren | Associate Professor | +4551299605 | |

| Schmidt, Jakob Linnet | PhD Fellow | ||

| Shamir, Avner | Associate Professor | +4521179329 | |

| Simonsen, Gunvor | Associate Professor - Promotion Programme | +4551299335 | |

| Skaarup, Emil | Teaching Associate Professor | ||

| Sonne, Lasse Christian Arboe | Associate Professor | +4535326957 | |

| Steinbach, Daniel | Associate Professor | ||

| Thomsen, Christian Ammitzbøll | Associate Professor | +4521179817 | |

| Vallgårda, Karen Asta Arnfred | Professor | +4520203861 | |

| Ward, Stuart James | Professor | +4535328164 |